Apprenticed to Ghosts: accountable for mending shadows….

Author: Julie Montgarrett

Abstract

This paper concerns my creative practice as research which questions the received histories of the beginnings of settlement of Van Diemen’s Land – 1803-1825. By way of drawing and embroidery, I aim to present ‘possibilities from uncertainties’- visual narratives like unfinished sentences which aim to unsettle fixed perceptions of the past. By questioning the ways that narratives might be constructed to fold back across time I hope to reveal worthwhile aspects of the present from visual and material shadows of the past; to visually question these connections without falsifying history, to create contemporary meanings in ways denied to historians. Like most artists engaged with narrative form, my research is fundamentally performative in both its production and audience reception. It begins through a process of divergent textual, visual and material methodologies which assist the development of a personal language shaped by the disciplines and traditions of drawing and embroidery. These strategies generate more ‘enquiries’ to be tested visually and materially, returning to critical and textual sources to drive the wider research process. These are adaptable methodologies informed, challenged, re-directed, and motivated by way of an unpredictable process; a contingent, performative practice driven by a circular methodology. My creative practice is an ‘attention to the process of creativity’ as defined by Merleau-Ponty. It is a form of inquiry into the phenomena of visual narrative through artistic, material and aesthetic means. This creative practice-based methodology conceives research as an enactive space of living enquiry, a performative, material ‘making visible/tangible’ production of meaning. According to Barrett and Bolt, ‘ the innovative and critical potential of practice-based research lies in its capacity to generate personally situated knowledge and new ways of modelling and externalising such knowledge while at the same time, revealing philosophical, social and cultural contexts for the critical intervention and application of knowledge outcomes.’ Further, they refer to knowledge that arises through intuitive understanding closely related to Bourdieu’s theories of a logic of practice, of ‘being in the game’ where strategies are not pre-determined but emerge and operate according to specific actions and movements in time. As such my works emerge slowly through the research process. They don’t appear immediately like photographs; they evolve unpredictably, reliant on particular material encounters and chance occurrences that emerge from process. Form and content are gleaned and cross-referenced visually, materially, and textually through wider research and reading as much as the process of making to generate often unforeseen narratives, meanings and outcomes. Significantly the methodology of the artist is driven by trial and error and is profoundly reliant on ‘process’ as well as speculation, or asking the question, ‘what if?’. Or perhaps better still, as Samuel Beckett said, ‘Ever tried. Ever failed. No matter. Fail again. Fail Better.’

To cite this article

Montgarrett, Julie. “Apprenticed to Ghosts: Accountable for Mending Shadows.” Fusion Journal, no. 7, 2015.

‘Dark times’ surround us when the past cannot guide us into the future.’

Hannah Arendt (Bird Rose 2004 p. 1)

For over two hundred years, Australia has sustained a carefully crafted national narrative which, as W.E.H. Stanner observed, “…may well have begun as a simple forgetting of other possible viewpoints, turned under habit and over time into something like a cult of forgetfulness practiced on a national scale.” (Stanner 2011 p. 24). If clear evidence of this phenomenon is needed, it can be readily found in one of the Nation’s most significant museums of remembrance – the Australian War Memorial in Canberra. It does not acknowledge the frontier violence and dispossession of the First Australians as a legitimate event, as a part of Australia’s history of war, despite significant reconciliation speeches by two Prime Ministers – Paul Keating‘s Redfern Address of 1992 and Kevin Rudd’s 2008 ‘Apology’ to the Stolen Generations.’(DFAT 2008) As Keating observed, this is one aspect of “a test of our self-knowledge. Of how well we know the land we live in. How well we know our history. How well we recognise the fact that, complex as our contemporary identity is, it cannot be separated from Aboriginal Australia.” (Keating 1992)

Many voices since the 18th century British invasion of ‘the great south land’ have called unsuccessfully for an acknowledgment of Aboriginal sovereignty and the sustained brutality and dispossession the first Australians have suffered since the colonial era destruction of their ancient high cultures. Nonetheless, as Henry Reynolds recently wrote:

The national narrative became one of a hard and heroic fight against nature itself rather than one of ruthless spoliation and dispossession. The squatter and the bushman became national heroes, sharing many attributes but appealing to different sections of the community. No one wanted to notice the blood on their hands. (Reynolds 2013 p. 16)

Australia is not and never was a country created in peace.

place settings: of country, circumstance and consequence

This paper addresses the performative aspects of my creative practice as research concerning the first two decades of this history of silences – the British invasion of Van Diemen’s Land of 1803. A distant past; a time of great but fragile possibility, and lost opportunity for a different future for the people of Tasmania’s First Nations. Twenty years during which the entire island was steadily transformed into a devastating war-zone as more settlers arrived to ‘take-up land’, as predatory roving parties worked across the island ‘bounty-hunting’ Aborigines. Those few settlers who had attained tentative understanding and fluency in language of the first Australians in Van Diemen’s Land were swept away. Indeed, continued arrival of unscrupulous, ambitious settlers resulted in the destruction of a fragile and ancient high culture at the hands of those intent on re-making themselves beyond the strictures of the British class system, to secure their own fortunes at any cost and by any means available.

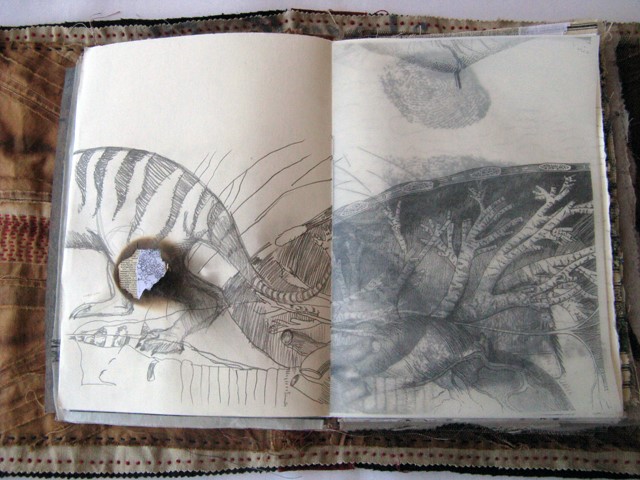

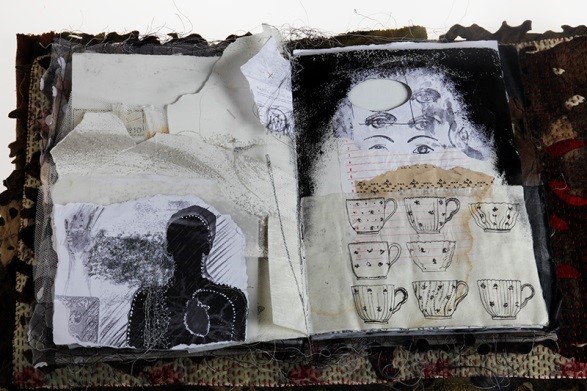

figure 1: Julie Montgarrett ‘if, IF is a question…’ 2011. Artists’ book. Photograph: Myles Prangnell

At the centre of this research is a silhouette and events that some call an invasion and others prefer to legitimise and call a ‘colony’. I have learnt to call this a complex, conflicted uncertainty – far more than a binary collision of cultures. The silhouette is perhaps my ancestor, my great, great, great grand Uncle – Jacob Mountgarrett (1773 – 1828). Irish-born, first ‘notorious’ Colonial Naval Surgeon and Magistrate, aside from a shared last name, I cannot be completely certain of our relationship. Two centuries distant, my paternal family tree ends abruptly – erased by fires in the Public Records Office of Dublin in 1923 that destroyed all documentation and turned any certainty of precise relationship to ash and doubt. Though Jacob and his brother James appear in my family tree, made visible by other extant archival ‘facts’, the Public Records Office fire has left a gap, an open space of doubt just beyond the confirmed branches of the family tree. This gap is also a space of some anxiety – of both seeming complicity in relation to the first brutal years of colonial ‘settlement’ and indeed to the euphemisms of slaughter revealed by the colonial archives – as much as it is also a need to ‘own up’ and to take responsibility for telling these stories and to make sense of these lives beyond a stale and stereotypically drawn historical veneer. As Robert Bollard asserts “we are a nation with little regard for its history.” (Bollard 2014 p.9) Perhaps this poor regard has arisen for some because close inspection of this history is confronting – a disturbing and distressingly complex encounter to navigate and unravel.

guessing games in borrowed spaces

Jacob Mountgarrett is one of four key characters who endured the catastrophic change of the era and who were responsible for a number of Aboriginal children including ‘Dolly’ Dalrymple Mountgarrett Briggs and her four siblings. Further details of their lives and others are scant, during a largely unknown and poorly recorded era – the first twenty-five years of British invasion of northern Tasmania.

They can be partly represented by drawing upon the limited facts and fragments of their circumstances, in order to begin ‘unpicking the seams’ of these characters’ disguises, as little more than shadows in the archive. Rather than allowing these figures to remain largely absent from the colonial era master narratives, we may instead recognise them as contributors to an imagined polyphonic narrative through commonplace objects and materials.

I aim to create visual and material encounters with this history through the fragile contingent mediums of both drawing and embroidery, in order to engage the interlaced roles of memory, imagination, and visual narrative beyond stereotype. This represents an attempt to underline absences; to create incomplete, deliberately uncertain visual narratives about the cultural landscape of the past and present, that explore the inter-subjectivities of remembering and forgetting of histories and customs, in order to unsettle received assumptions shaped and imposed by the blind-spots in dominant cultural knowledge of non-Aboriginal Australians. Absences that cannot be resolved or clearly identified, anxiously hover on the edge of sense and meaning, and

perhaps in the open spaces; the aporias between these culturally known images, arranged in odd sequences, displaced in defiance of a logical narrative and clear meaning, a perception of something else, something not clear or complete that might arise. These absences are perhaps akin to Robert Young’s interpretation of Homi Bhabhas’ hybrid and problematic Third Space, which:

is not a space nor, is it a place. If anything it is a site, but even then it is not a site in the sense of a building site, somewhere bounded and fixed that can be located with the right coordinates with your Satnav/GPS on a map . . . a place which is not a space because it is the site of an event, gone in a moment of time. . . The third space is also a site in the sense of a situation, and, for the subject, a site’s other sense too, that is, of care and sorrow, grief and trouble: to make site is to lament and mourn. For the third space is above all a site of production, the production of anxiety, an untimely place of loss, of fading, of appearance and disappearance. (Young 2008 p.82)

Without a conventional narrative sequence and thus implied ‘meaning’ might suggest something of the fragile, tenuous lives historically erased, of those who lived in the cross-fire of this war-zone: As a task toward making the invisible somehow present, if never fully imagined, recognised or known. Echoing Alison Ravenscroft, “that the truth of images might lie in what fails to appear as much as what is in view.” (Ravenscroft 2012 p.11) So we might acknowledge that these imagined characters are always silhouettes shaped by our non-indigenous cultural perspectives and expectations. Like Ravenscroft, I too am interested in the necessity of fragments and the gaps in representation, in the silences, doubts and places where representation fails, and crucially in the stitches that non-indigenous Australian readers of textuality have made attempting to cover over these gaps by reckoning and calculating the death-toll and trauma of colonisation that defies all expression. “The fragmentation, gaps and silences are the story” (Ravenscroft 2012 p. 13)

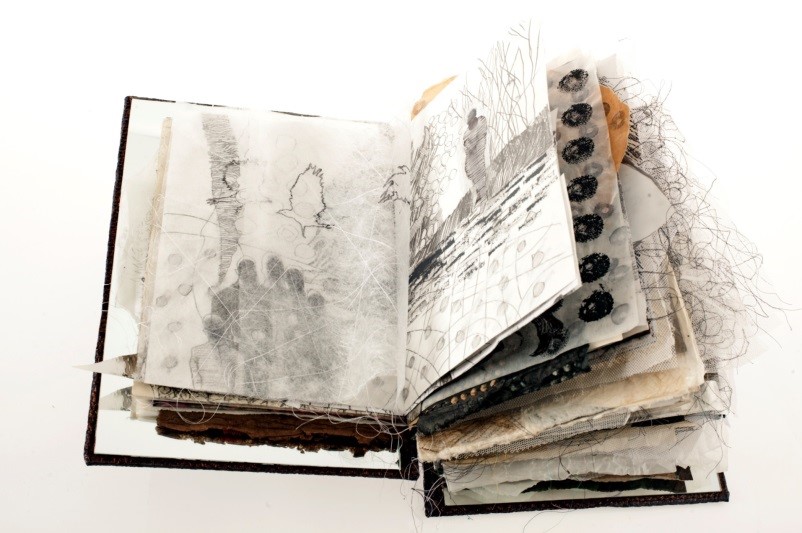

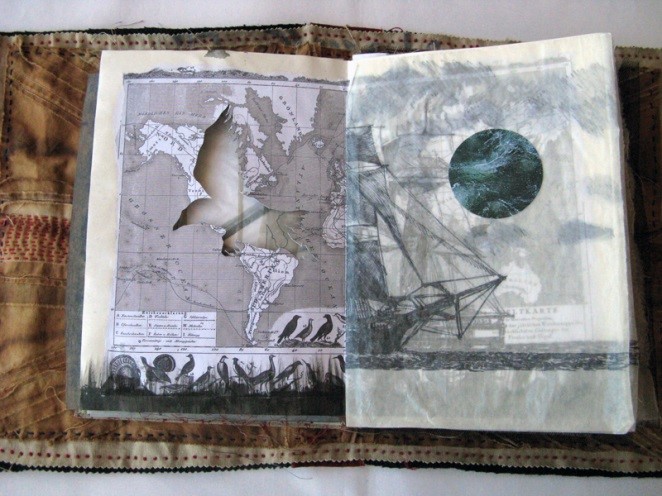

figure 3: Julie Montgarrett, Jacob Mountgarrett’s Sketchbook – Drawn, printed, machine stitched tulle, collage, bush-dyed sail cloth, Navy wool cloth , hand stitched Union Jack pillow. Pages 37/38

‘aesthetic practices that allow such strangeness to be’

(Ravenscroft 2012 p. 1)

Despite the violent narratives of this history and fact of the larger arc of the genocide and destruction of Palawa culture, more subtle yet plausible elaborations of the possible circumstances of some of these lives might better locate them amidst the brutal events of this era. We might shape a glimpse of their lives between silhouettes and shadows with tenuous and fragile threads amidst the gaps in this history. As Lynette Russell’s research into the vital roles and relationships between the authority of British settlers, sealers, Straitsmen and Australian Aboriginal sealers and whalers in the Southern Oceans in the nineteenth century demonstrates,

epistemological dichotomies have fostered a number of overly simple interpretive paradigms. These include invasion and resistance and accommodation, acculturation and defiance, and so on. These heuristic devices based on imagined dichotomies categorize the world into a comprehendible black and white pseudoreality, simplifying and homogenizing complexity, variability and uncertainty. (Russell 2012 p. 20)

My attempts to trace the lives of these individuals during this period of escalating warfare, have required an envisioning of circumstance, an imaginative piecing together of few mismatched, awkwardly contradictory, historical ‘facts’ and fragments to shape inevitably fragmented, ragged visual narratives. In order to create any sense of these lives and by comparison to perhaps reflect aspects of our own, Ross Gibson suggests that, “We need to propose ‘what if’ scenarios that help us account for what has happened … so that we can better envisage what might happen. We need to apprehend the past”. (Gibson 2007) Further, Gibson suggests that this requires imagination, involving “a readiness to incorporate the unknown … when one encounters evidence that’s in

smithereens”. (Gibson 2007 p.106)

figure 4: Julie Montgarrett Bridget’s (Edwards) Mountgarrett sketchbook – page 47/48. Drawn, printed, machine stitched tulle, collage, bush-dyed wool felt, quilted vintage cotton printed pillow. Pages 47/48

navigating tensions: between fraught fictions and fragile facts

Similar methodologies and strategies that enable the negotiation of collective histories and uncertain, fragile ‘facts’ can be found in the works of a number of internationally respected artists most notably – William Kentridge, Rozanne Hawksley and Julie Gough – whose works similarly address the history of Van Diemen’s Land. Each artist’s works bear witness to respective histories that haunt the present while also engaging a number of methodologies to address the ways that the past continues to infect the present. Each addresses ideas of memory, visual narrative and collective histories, recognising, as Inga Clendinnen asserts, that “democratic peoples need true stories about their past’ and ‘a responsiveness to a multiplicity of stories catching the experiences of different individuals in different situations.” (Clendinnen) In recent decades the role of memory, imagination, and narrative in shaping individual and community identities, in a process of remembering and forgetting histories and traditions, has given rise to new forms of narrative in visual arts practice reflected in these artists’ respective practices. As James Boyce proposes in respect of Australian Colonial history, ‘those who don’t share the constraints of history’s empirical practices, who can bring an imaginative response to these complex cross-cultural relationships are the artists, storytellers, community builders (who) have perhaps the more important calling.’(Boyce 2008 p. 65) In light of this, we may consider that the past is neither a threat nor an accusation, rather it is an opportunity to reinterpret histories by engaging doubt as an ally – seeking other stories to challenge our habits of false assumptions and certainties born of cultural blindness. In the absence of fixed ‘meanings’ a perception of something else, neither clear nor complete might arise; something erased from history. This element of doubt is a vital element in a process of questioning and challenging received histories which neglect to address a more complete understanding of the complex circumstances of history’s little known protagonists. Doubt may offer a means of closer

scrutiny of their relationships which in turn might impact upon the perceptions and legacies of our collective histories.

figure 5b: Rozanne Hawksley, Intuitive and Internal http://www.textileartist.org/intuitive-and-internal/

Kentridge, Hawksley and Gough engage the basic human need to acknowledge tradition and history – the very things twentieth Century Modernism’s purist, Universalist aesthetic aspirations had denied and which has increasingly infected the content and form of contemporary arts of the past two decades. These artists, working through complex narrative series and exploiting the contingencies of a creatively mutable material process demonstrate a movement towards new forms of visual narrative that investigate significant social and political issues of identity, fragility, disadvantage and disenfranchisement. Through drawing, embroidered assemblages and installations respectively, their works are evidence of ‘. . .all those excluded, marginalised voices, unheard

testimonies and objects imbued with specific historically located and narrated significance crowded into art’s buildings and spilled out into hitherto non-art sites and streets, like so many tokens of reminiscence brought down from a thousand attics after decades of being stowed away.’ (Farr 2012 p.13)

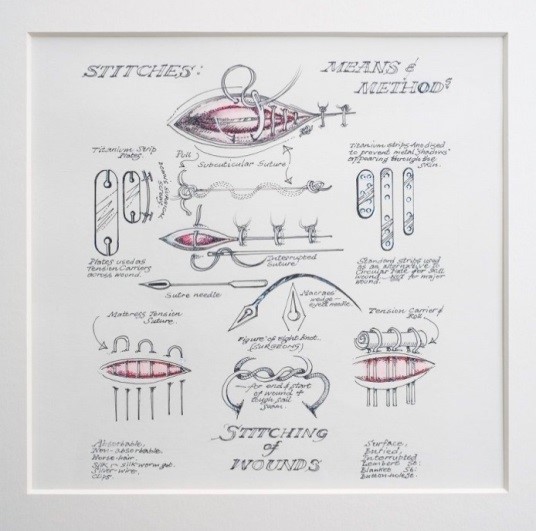

Hawksley’s textile assemblages address in subtle and complex ways poignant aspects of the human condition through emblems and symbols of commemoration and memorialization. Her works bear a particular focus on the nature and meaning of war across the gendered divisions of labour and duty through personal, community and national realms. She summons the enduring traumas of war through relics that are “carefully crafted, baroque, theatrical and beautifully made. The subject matter is challenging and provocative, communicating intense feelings and emotions, such as pain and anguish, that so often have no voice of their own.” (Hawksley 2015)

figure 6a: Rozanne Hawksley The Seamstress and the Sea series http://www.rozannehawksley.com/USERIMAGES/WM6.JPG

figure 6b: Rozanne Hawksley The Seamstress and the Sea series http://www.rozannehawksley.com/USERIMAGES/stitchesmeansandmethodsand%20stitching%20of%20wounds2006.jpg

One of her best known and loved works (figure 5a) currently displayed in the Imperial War Museum, London, Pale Armistice was made in part in response to the First World War and is ‘[F]ashioned out of gloves – those that are worn, or brand new, wedding gloves and those worn by officers — they represent all those who have been touched by war.’ (Hawksley 2014) It is also a piece that subverts a traditional symbol of commemoration and makes us question the meanings of remembrance and the role physical objects play in constructing our interpretation of events lost to living memory. Hawksley’s fragile textile assemblages interrogate and exploit the ‘work’ of cloth in culture – the dynamics of luxurious fabrics in shaping religious iconography or the complex textile structures of military uniforms, and the significance of each in national and domestic rituals. Her complex, intimate works explore the production roles and divisions of labour in women’s work and the ways these reflect social patterns of disadvantage, religious orthodoxy and community cohesion.

Rich in allegorical references, her work charts an odyssey encompassing the universal and intensely personal. Recurrent themes are the fragility of the human condition and the immorality of war … any study of her work will stimulate, provoke, inspire and mystify. (Hughes 2015 p.3)

Gough’s works refer in part to the cultural traditions of Tasmanian indigenous first Nations and their histories of genocide, dispossession of country, culture and language. She says, “My art and research practice often involves uncovering and re-presenting historical stories as part of an ongoing project that questions and re-evaluates the impact of the past on our present lives. My work is concerned with developing a visual language to express and engage with conflicting and subsumed histories. A key intention is to invite a viewer to a closer understanding of our continuing roles in, and proximity to unresolved National stories- narratives of memory, time, absence, location and representation. (Gough 2015) Dark Valley, 2008, constructed from pieces of coal refers to the traditions of shell necklace making and her family’s connections to coal mining. Wearing these works she is reminded of the present weight of history. (Gough 2012)

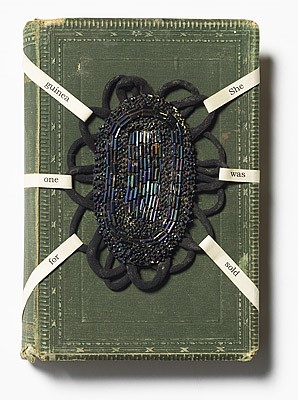

figure 7: Julie Gough “She was sold for one guinea” 2007, Found beaded decoration and book on wooden shelf 12 x 13.5 x 20 cm http://www.utas.edu.au/colonialism/conferences-and-symposia/empire,-humanitarianism-and-non-violence-in-the-colonies

Through other works Gough adapts found objects such as cuttlefish bone, tea tree and shell, and found texts into works to create links across time to the encounters of her ancestors with the colonial invaders of the nineteenth century. She was sold for one Guinea, 2007 (figure 7) is a direct reference to the life of her ancestor, Worete.moete.yenner, the mother of Dalrymple Briggs, conjured with a found book, tied shut with a woman’s antique, beaded mourning-dress motif. As Gough says of the making of many of her works, “My major motivation to make art is aligned to my ongoing curiosity and concern about Australian history, particularly the colonial period and cross-cultural contact and interactions in the 19th century,”. Gough has gone further, noting “I am trying to unravel what happened here and reconstruct what was often not well recorded or was even purposely erased or silenced by the colonising majority in terms of Aboriginal history.” (Gough 2014)

figure 8: Julie Gough Dark Valley, Van Diemen’s Land 2008 coal, http://www.artgallery.nsw.gov.au/media/collection_images/3/348.2008.a-c%23%23S.jpg Couch NGA

figure 9: Julie Gough, Some Words for Change, installation, Freycinet Peninsula. photo Simon Cuthbert. http://www.realtimearts.net/data/images/art/16/1659_tudor_gough_02.jpg

Like Hawksley and Gough, William Kentridge also addresses traumatic histories, those of pre- and post-apartheid South Africa and Namibia. Kentridge explores process akin to re-mapping terrain and events through drawing as impetus to interrogate that difficult recent past for the present. As Ann Rutherford (2013) wrote in relation to Kentridge’s work:

If you want to kill a man draw a rifle;

If you want to kill a people draw a map.

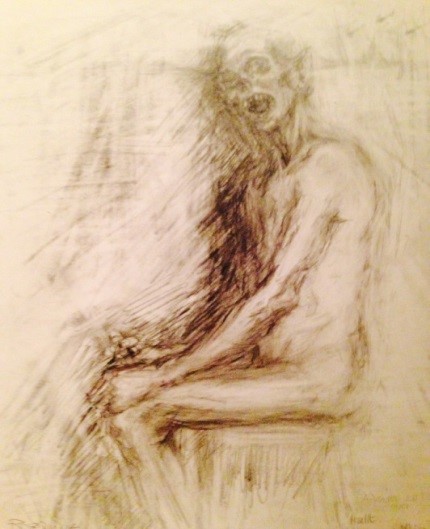

Drawing is the foundation and driver for all of Kentridge’s work: animations, sculptures, prints, tapestries and production designs for Opera, which explore universal themes of resilience, love, redemption and survival against the wider sweep of violent, unbearable histories. They record the Apartheid Regime in South Africa, the subsequent Truth and Reconciliation Commission, and the insidious impacts of Colonialism and post-Colonial aspirations more generally across the world.

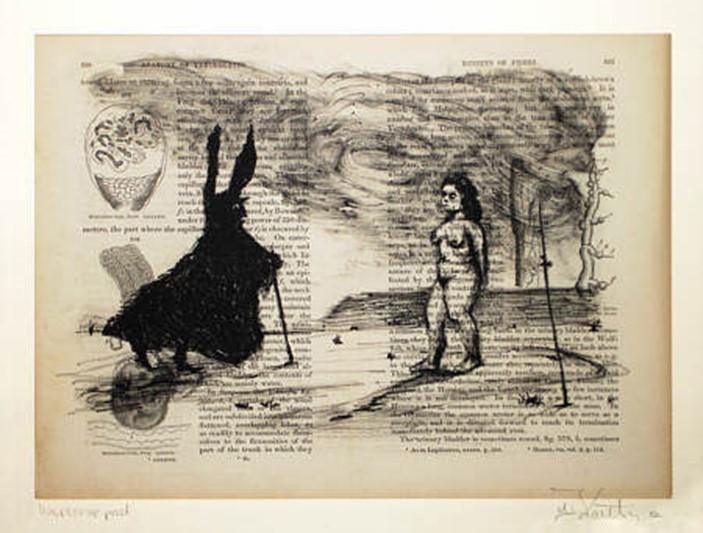

figure 10: William Kentridge, 2006. Anatomy of Vertebrates, Lithograph printed on Collaged text page 22 x 28.5 cm edition 30. http://www.artthrob.co.za/06apr/listings_intl.html

Kentridge has explored idiosyncratic and divergent animation processes throughout all his ambiguous and confronting narratives. Indeed, encountering William Kentridge’s early animations of smudged charcoal lines and ghostly erasures trace gestures that negotiate traumatic historical events through rhythm and repetitions to reveal and conceal the actions of his improvisational decision making process is mesmerising, as audiences internationally attest.

in/visible mending

As the artists demonstrate, reassembling, re-ordering, re-scaling motifs, repeating fragments and visual and material clues can unexpectedly generate numerous stories and emergent meanings. These act, like unfinished sentences or propositional visual narratives about the past and present, as vehicles to explore what William Kentridge describes as a process where ‘the very mechanism of vision is a metaphor for the agency we have, whether we like it or not, to make sense of the world.’ (Christov-Baragiev 1999 p. 35)

figure 11: William Kentridge, 2006. Anatomy of Vertebrates, Lithograph printed on Collaged text page. 22 x 28.5 cm edition 30. http://www.artthrob.co.za/06apr/listings_intl.html

These approaches to practice mirror mine in that, as Kate McCrickard describes ‘Kentridge’s oeuvre may be best described as a mass of unbuttoned fragments that are never fully fastened together. He channels his visual world through a conduit of disjunction and incomplete viewing’. (McCrickard 2012 p. 45). Kentridge observed that the mechanics of puppetry – a lessening of control between hand and eye suggested the value of tearing paper to blunt purpose and direction was a valuable addition to his performative working process. In that it operated, ‘to disrupt habitual line and open up holes in our vision field, bringing vividness and variety to our perception of things … tearing breaks and bothers identity. It pushes the viewer to work at recognising form through association and memory, thus evoking a sense of looking askance or indirect vision, flickering between seeing and knowing’. (McCrickard 2012 p. 45)

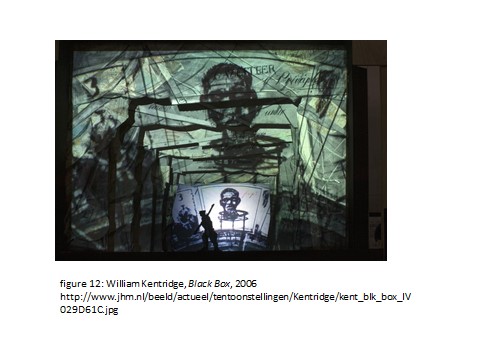

Kentridge’s Black Box work – Trauerarbeit: means grief work in English – is a perfect descriptor of all three artists’ work and equally informs my own undertakings as another form of grief work; a work of mourning that addresses the dispossession and murders of early colonial history of Van Diemen’s Land and the rocky and uncertain shoals of a contemporary Australia that remains uncertain of its own collective identity.

This notion of ‘grief work’ aligns with Susan Radstone’s ‘memory work’ which in turn arose from Freud’s theories of ‘dream-work’. (Giddons 2013 p. 150) In summary, Freud’s studies address the basic human need to condense, screen and consolidate knowledge and experience via dreams. In these works – it is an imaginative process that addresses these unresolved experiences and in many respects these artists ‘grief works’ operate in similar ways. Each artist exploits the unpredictable contingencies of their interdisciplinary material practices across fields of drawing, animation, installation and textile towards new complex series created in defiance of conventional narrative sequences with logical expectations.

Each artist’s methodology coincides with my own in as much as they follow a performative creative process that engages uncertainty and doubt pursuing outcomes that are not known at the outset, but are allowed to emerge thorough the coincidences of materiality and concept as a fundamental driver of the research investigations. Their subjects are also intentionally difficult historical re-interpretations of social injustice and hypocrisy – the insidious impacts of Colonialism, the agonies of South Africa’s apartheid regime and the legacies of frontier and Imperial Wars across centuries.

Each artist’s methodology coincides with my own in as much as they follow a performative creative process that engages uncertainty and doubt pursuing outcomes that are not known at the outset, but are allowed to emerge thorough the coincidences of materiality and concept as a fundamental driver of the research investigations. Their subjects are also intentionally difficult historical re-interpretations of social injustice and hypocrisy – the insidious impacts of Colonialism, the agonies of South Africa’s apartheid regime and the legacies of frontier and Imperial Wars across centuries.

Encountering and interpreting these artists’ works as unexpected narratives and fragmented patterns of coincidence dependent on individually framed cultural memory and bias requires a complicity on the part of the viewer. In the absence of fixed ‘meanings’, these histories can be re-imagined by each artist and skilfully crafted to exploit the visual and material storytelling potential inherent in the forms to disrupt received historical narratives to create contemporary meanings without falsifying history, and in ways that historians are denied.

temporary alignments: fragile facts and fraught fictions

My creative practice as research methodology conceives research as a performative space of living enquiry; an encounter as an enactive participation of material ‘making visible/tangible’ and making meaning, as Merleau-Ponty asserts. (Merleau-Ponty 1993) Barrett and Bolt elaborate this idea as,

the innovative and critical potential of practice-based research which lies in its capacity to generate personally situated knowledge and new ways of modelling and externalising such knowledge while at the same time revealing philosophical, social and cultural contexts for the critical intervention and application of knowledge outcomes. (Barrett & Bolt 2005 p.2)

This refers to knowledge that arises through intuitive understanding that guides performative processes closely related to Bourdieu’s theories of a logic of practice, of “being in the game” when,

caught up in the ‘matter at hand’, totally present in the present and in the practical functions that it finds there in the form of objective potentialities, practice excludes attention to itself (that is to the past). It is unaware of the principles that govern it and the possibilities they contain; it can only discover them by enacting them, unfolding them in time. (Bourdieu 2000 p. 92)

Bourdieu’s game is one where strategies are not pre-determined but emerge and operate according to specific actions and movements in time as an active negotiation and even perhaps a negation, of habitus. Habitus, Bourdieu asserts is symbolic and accounts for the inculcated continuation and acceptance without question of the dominant culture “in the form of durable dispositions.” Bourdieu asserts habitus acts to :

incorporate the objective structures of society and the subjective role of agents within it. The habitus is a set of dispositions, reflexes and forms of behaviour that people acquire through acting in society … It is part of how society produces itself. (Bourdieu 2000 p.19)

According to Bourdieu it is habitus which causes our collective disregard for our own history.

My creative practice and that of Gough, Hawksley and Kentridge is necessarily an un-packed swag of intuitively navigated uncertain, integrated performative means and methodologies. As Sullivan (2010 p. 245) proposes, a methodological uncertainty is legitimate, and fundamentally important to creative practice:

…contradiction, conflict and opposition are useful states of mind. Indeed these attitudes are necessary in adopting a creative and critical stance for doing visual arts research. In practical terms, whether producing artworks or planning research, there is a need to reconcile differences and rationalise difficulties. However as with art and research it is often from experiences that are simple and complex, precise and uncertain, that the most insightful outcomes are revealed and the most important questions arise. Therefore, it is not necessary to assume that theories are neat, practices are prescribed, that all outcomes can be predicted or that meanings can be measured. In fact, it is the opposite that is more likely reality. The messy resistance of new understanding relies on the rationality of intuition and the imagination of the intellect, and these are the kind of mindful processes and liquid structures used in art practice as research. (Sullivan, 2010 p.245)

Kentridge describes this process of methodological performative uncertainty, of constructing meanings intuitively and imaginatively through creative performative practice as “a slow motion version of thought. That what begins with a certain intention does not end up that way.” (Kentridge 2013 )

“Absence of presence is not presence of absence” Fiona Foley

(Genocchio 2001)

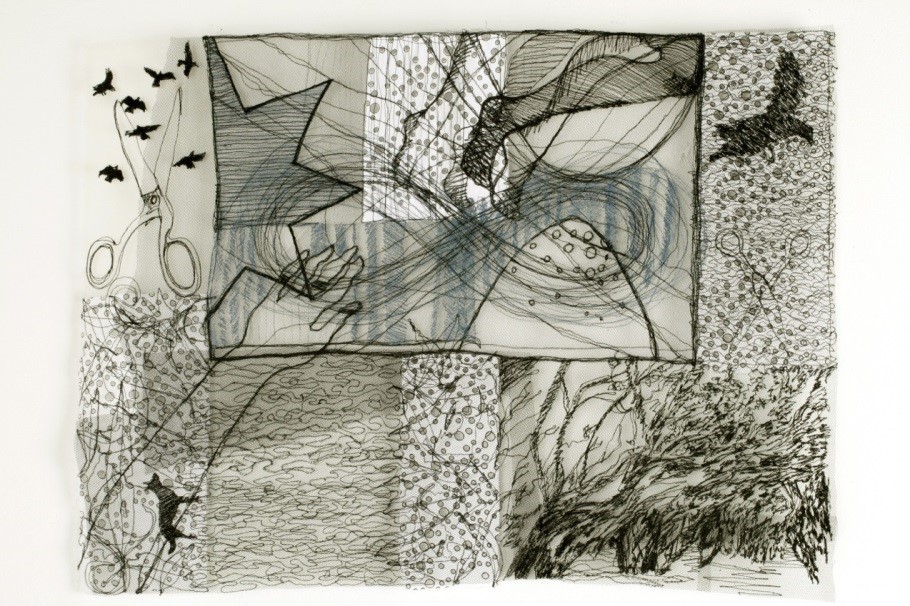

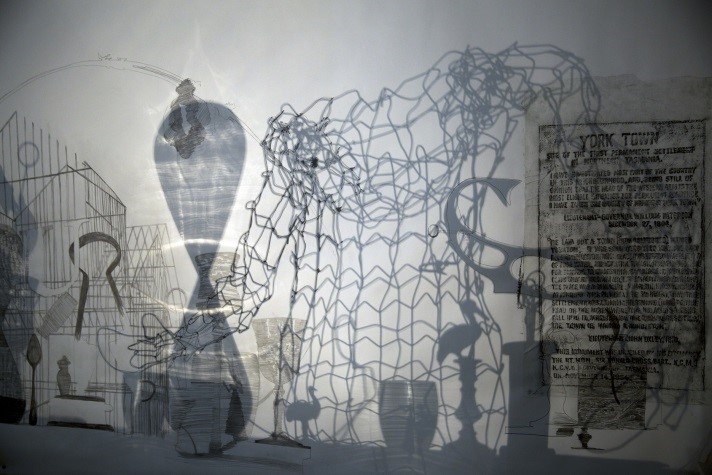

My research employs Ravenscroft’s concepts of the fragmentary remains of this past, “the gaps in representation, shaped by our nonindigenous cultural perspectives and expectations” that generate in the silences and “places where representation may be said to fail, and crucially … in the stitches that non-indigenous Australian readers of indigenous textuality tend to make to cover over these gaps” (Ravenscroft 2012 p.9). My drawings of shadows of ‘colonies’ of found commonplace objects directly and indirectly inform embroideries as fragile stitched line drawings that build ‘lace-like’ panels and which create further shadows that move across and throughout the installations of objects and drawings on the wall. Their instability aims to generate imagery that can imaginatively refer to and disrupt the habits of ‘stitching over’ the gaps and omissions that Ravenscroft suggests have plagued the past and remain so resilient in the present.

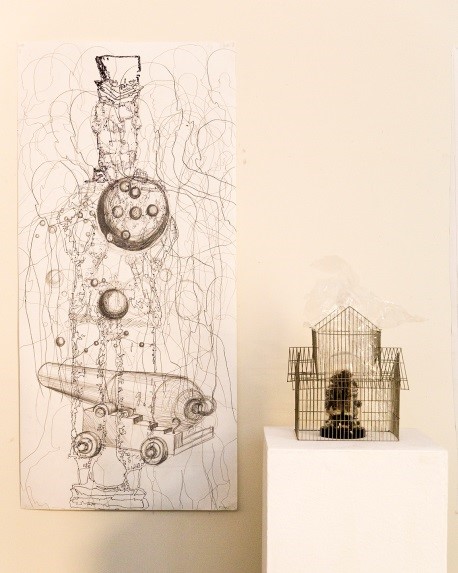

Images are first gleaned from on-site creative practice at historic sites in Tasmania and later extended and re-envisioned as forms in the Studio. These are grouped as a series of ‘sketchbook-like’ books or ‘pattern books’ to create a lexicon of fragmentary images. This initial stage of the research relates to traditional artists’ research tools which include visual diaries, observational and imaginative drawing and other devices of visual languages such as fragmentation, collage, spontaneity, chance and artists’ book-forms. Although the concept of the fragment is a key feature of contemporary visual languages and culture established with the rise of Modernism, it is equally fundamental to the character of this research due to the fragmentary nature of the majority of archival information available in respect of this early colonial period. The early Modernist artists adopted and exploited a fractured visual order collaging the scraps and clippings from daily life as signs and symbols of a world ‘fractured’ and in despair, seeking emblems of remembrance in mourning the destruction of the authority of faith and stability of the previous century in the aftermath of the First World War. Half-a century later, the rise of Postmodernism celebrated fragmentation as emblematic of a freedom and escape from fixed systems of order. (Hawthorn 2000)

The lexicon of fragments generated through the first stage of the research has been adapted as both a sign of mourning about the destruction of the past colonial era and as a form of bricolage. As a form of bricolage, the fragments in combination may operate freely, and unexpectedly function as an initial impetus for constructing more complex hybrid combinations of elements within works. The elements can shift emphases and change meanings that may be modified, consolidated or overturned. Kentridge notes that the “uncertain and imprecise way of constructing a drawing is sometimes a model of how to construct meaning. What ends in clarity does not begin that way.” (Christov-Baragiev 2007 p. 126) The fragments operate as a strategy toward innovation and interruption of particular readings of motif, material and sign. It is this particular performative transference that interests me – the accidental and often improbable connections that can arise; and the unplanned disruptions of signification that sometimes result.

figure 15: Julie Montgarrett Sketchbook Imagery enlarged and re-drawn and re-combined. Photograph: James Farley

Such performative creative practice research ‘methodology of chance occurrence’ lies at the centre of my research practice. Through the contingent process of drawing and embroidery in which, unlike a photograph, images do not appear immediately rather they evolve erratically through varied temporalities as hybrid fragmentary images suspended in ambiguous, even improbable relationships and illusions of space. As David Musgrave, Research Fellow at Chelsea School of Art, UK asserts, drawing has an “entanglement with language (it ‘describes’ something; there is a flash of energy from image to referent that doesn’t result either in their coinciding or estrangement) and its ability to elicit something less easy to articulate in words, something that happens in

the blind spots of representation.” (Kovacs 2007 p. 209)

Viewers witness the juxtaposition of visual and material elements gleaned from diverse sources – the worlds of nineteenth century anatomy and science, museum specimens and artefacts drawn on-site, old encyclopaedias, school stamp sets; textile pattern history, cartography, ethnography, colonial illustrations and naval histories among others. From sketchbook to book, elements reappear in different combinations – a figure; an ordinary gesture; a circumstance; a shadow – the repetitions may imply another account – like the banal fragments of some kind of incomplete fable from which some meaning might be made by the viewer. A fragment that may suggest a larger narrative, as Walter Benjamin asserts, is a characteristic of modern allegory (Buck-Morss 1989).

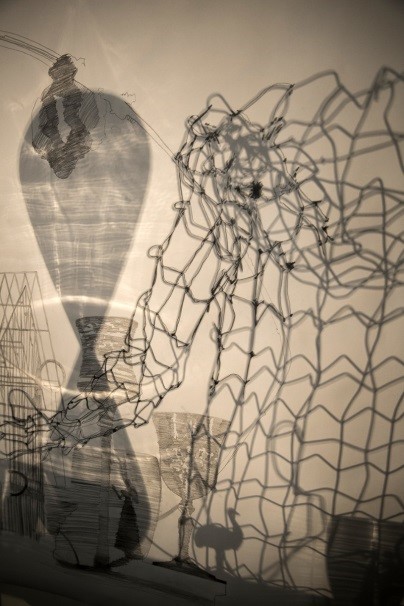

figure16: Julie Montgarrett Shadows from Colonies of Objects cast shadows drawn to wall 2015 Photograph: James Farley

The second stage of the research involves a further re-drawing and tracing at a far larger, life-size scale than the initial lexicon of images. Such images become figurative elements towards a final body of work consisting of a complex shadow-filled installation of objects, drawings and lace-like screens that includes the sketchbooks as a form of ‘archive’ on plinths. Grouped collections of objects similar to those of the Colonial period occupy other plinths within the gallery space as ‘colonies’. These are further altered, re-aligned and re-combined many times in an entwined and braided process.

I am interested in Paul Carter’s ideas from ‘Dark Writing, of ‘moving within the constructions of place’. He suggests new approaches to regenerating practice and reinvigorating our thinking about place and time, and recommends:

“a new thinking (and drawing) practice” [which] does not abandon the line but goes inside it. The line is always a trace of earlier lines. However perfectly it copies what went before, the very act of retracing it represents a new departure.” (Carter 2009 p.8)

Carter’s ideas have led my research towards a specific investigation of the ways that nineteenth century proto-Photographic tools, most especially shadows as an absence of light can identify when captured as different marks and rhythms of shapes, textures, tones and even negative spaces because,

Within every line there is a braid of other lines. The one line that emerges from this quiver of intentions is the reduction of a multiplicity of orientations, invocations, and prayers. To be conscious of this is a start. By re-figuring the line as a meeting place of ambiguous expectations, as the trace of a mental journey – so that drawing the line is not an act of cutting off and conclusion but a process of directed movement, the discourse of place making can be practically re-oriented. (Carter 2009 p. 8)

These strategies are not simply inimical. Each practice traces process, recording chance and repair offering opportunities to enhance a sense of fragility and to discover unpredictable silhouettes and surfaces that may guide the ‘thinking/testing’. As Nigel Hurlstone states, “the processes of both drawing and stitch may … be seen to act as mediators between the hand and the eye, and through that mediation, we are able ‘to impart the sensation of things as they are perceived and not as they are known”. (Hurlstone 2012 p. 36)

figure17: Julie Montgarrett Drawings taken from shadows become lace-like embroideries (above) which in turn cast more shadows across colonies of objects for further drawings

Importantly the thinking/making is visual, material, critical and circular. It is an on-going performative process of creating and re-creating imagery to address this history by drawing from drawings toward embroideries and textile to ‘stitch over’ Ravenscroft’s gaps in understanding, by creating further imagery.

Despite the freedom this methodology affords, I am aboard a painfully slow and unreliable vessel, seeking the re-assurance of a life-raft, any life-raft as the winds change, and my trust in certainties becomes problematic when surrounded by confronting narratives and ‘difficult stitching over’. Am I Captain (an authority responsible for outcomes); navvy (menial labourer); navigator (a reader of charts and conventional maps); shanghaied sailor (kidnapped and resistant participant); ships’ surgeon (a skilled craftsman or perhaps… a butcher); or merely regal/mermaid/artist figure-head clinging to the bow of a Narrenschiff – a ship of fools or worse – a lesser life-form, the ship’s unpaid menial worker, the rat catching cat?

None of these masks alone applies – each is each a different facet of my practice. I am obliged of course to leave it to the audience who encounter these works long after the performance is done and the studio vacated. It is they who are left to decide as to which of these masks were worn in the performances behind this creative practice as research – the resulting work and explanations. As any creative arts practice inevitably begins as a transitive verb, as that of an action enacted upon something, in this case as installation, it is equally something that must necessarily end with an intransitive verb – an affect – you may be unconvinced or thoughtfully pleased by the encounter. Either way, if these art works as research are to attain a legitimate status as creative practice, as a ‘completed performance’ they must attain an effect or meaning with an audience.

What I do know, however, my preferred mask is that of artist, as Kentridge says: “I am only an artist. My job is to make drawings, not to make sense.” (Kentridge 2013)

The works aim to make visible and address the gaps in our ‘habitus’ – the absence of understanding that generated fraught and brutal relationships between non-Aboriginal and First Nations Australians that continue to haunt our shared cultural domains, despite more than 200 years through visual ambiguity and paradox in multiple, intersecting, fragmented visual narratives. Alison Ravenscroft and Boyce identify the need for us to acknowledge the extent of what we do not and cannot know of both the historical and the indigenous cultural landscapes.

As Stanner reported many decades ago, there are things in Aboriginal cultures and histories that cannot be known, that representation is only partial and incomplete: some things escape representation. “A silence and gaps must be allowed to remain, the silence into which things must fall, places of unknowability”. (Ravenscroft 2012 p. 18)

Too often, non-indigenous cultural perspectives assume that colonising and settler impulses and perspectives that experienced indigenous cultures as alien remain only in the past. But as Ravenscroft observes, even today indigenous cultures “remain in significant ways profoundly, even bewilderingly strange and unknowable within the terms of (these) settler epistemologies.” (Ravenscroft 2012 p.1) Ravenscroft and Boyce also suggest that those who don’t share the constraints of history’s empirical practice might possibly find new ways of seeing that accept and navigate difference “as a stranger or foreigner might, not to trespass or colonise as versions of self but instead acknowledging radical difference – even sovereignty?” (Ravenscroft 2012 p. 1)

I also share Ross Gibson’s (2014 p.4) view of the archive as a conduit to a past that “is no gone thing”. Gibson (2014) claims history as

‘an unclosed action. Something generative and unstable. Not something settled. It follows that the archives used by historians and memory keepers must be designed and kept open in ways that encourage a kind of unstinting performance by and amongst the stored traces and remnants of the past. The traces must be activated endlessly and promiscuously.’

These views of history as an ‘unstinting performance’process of invention aligns closely and informs my creative practice methodology. Through open-ended methodologies and material contingent practices, I hope to unsettle respectfully and rearrange imaginatively this evidence of the past through a visual and material process that triggers re-shaped models of ‘remembering’ to make new meanings about the past in the present. I agree with Gibson (Gibson 2014 p.4) that there should never be a “shut-up proof that concludes the tale” of history.

As noted earlier, my works emerge slowly through the research process. They don’t appear immediately like photographs; they evolve unpredictably, reliant on particular material encounters and chance occurrences that emerge from process – of forms and details often subliminally perceived and noted that later ‘surface’, transformed and re-scaled in new combinations and relationships. Many images and elements dissolve and re-surface in tandem with material encounters towards a new kind of translated space of the past in the present.

I am not an illustrator of certain conclusions about our colonial history.

Creative practice generates through performative practice its own unique forms of knowledge as material forms outside of traditional academic disciplines and methodologies. Within the studio meanings can be generated through uncertainty and flux – the materiality becoming the actual guide for the outcomes of the unscripted performance of tacit understandings.

In conclusion, I consider Kentridge most effectively locates the purpose of this particular performative creative practice as research:

To say that one needs art, or politics, that incorporate ambiguity and contradiction is not to say that one then stops recognizing and condemning things as evil. However, it might stop one being so utterly convinced of the certainty of one’s own solutions. There needs to be a strong understanding of fallibility and how the very act of certainty or authoritativeness can bring disasters.”(Kentridge 2013)

This early Colonial period is currently undergoing significant re-examination and is now the subject of major debates and discourse by these historians, writers and cultural theorists among others. This performatively generated research is a contribution to that discourse. Or as Samuel Beckett said, ‘Ever tried. Ever failed. No matter. Fail again. Fail Better.’ (Bloom, 2008 p. 46-49)

Works Cited

Barrett, Estelle, Bolt, Barbara. Chapter 1, “Introduction”. Practice As Research: Approaches to Creative Arts Enquiry. Eds. Estelle Barrett, Barbara Bolt. London: I.B.Tauris, 2005. p.2

Benjamin, Walter. “The storyteller: reflections on the works of Nikolai Leskov”, in Illuminations, Ed. Hannah Arendt (transl. Harry Zohn) London: Fontana Press, 1992, p.83; p 89

Rose, Deborah Bird. ‘Introduction: Into the Wild’. Reports from a wild country: Ethics for decolonisation. UNSW Press, 2004, p.1

Bloom, Harold, “Waiting for Godot”. Samuel Beckett (Modern Critical Interpretations). New York: InfoBase Publishing. 2008. pp. 46-49.

Bourdieu, Pierre. The Logic of Practice. Stanford University Press, 2000. p. 92; p.19

Boyce, James. “Chapter 2: What Business Have you here?” in First Australians: An Illustrated History, Eds. Marcia Langton, Rachel Perkins.Melbourne: Miegunyah Press, 2008. p 65

Buck-Morss, Susan. The Dialectics of Seeing: Walter Benjamin and the Arcades Project. Studies in Contemporary German Social Thought. Boston: MIT Press, 1989. p.18

Carter, Paul. Dark Writing: geography, performance, design. USA: University of Hawai’I Press, 2008. p. 8

Clendinnen, Inga. True Stories, Boyer Lectures Introduction. 20 December 1999. http://www.abc.net.au/rn/boyerlectures/stories/1999/1715598.htm October 18 2013

Farr, Ian. “Introduction: Not Quite How I Remember It”. Memory, Documents of Contemporary Art. Ed. Ian Farr. London: Whitechapel Gallery /MIT Press, 2012: p. 13

Genocchio, Benjamin. Fiona Foley: Solitaire. Piper Press, 2001: p.28

Gibson, Ross. “Places Past Disappearance.” Transformations 13-1 (2006) Retrieved June 2015 http://www.transformationsjournal.org/journal/issue_13/article_01.shtml

Gibson, Ross. 26 Views of the Starburst World: William Dawes at Sydney Cove 1788-91. UWA Publishing, 2012: p.106

Giddons, Joan. Contemporary Art and Memory: Images of Recollection and Remembrance. London: IB Tauris, 2013: p.150

Hawksley, Rozanne (2015). Rozanne Hawksley website, retrieved on 4 August 2015 from http://www.rozannehawksley.com/

Hawksley, Rozanne (2014). Pale Armistice by Rozanne Hawksley at Royal Museums Greenwich website, retrieved on 4 August 2015 from http://blogs.rmg.co.uk/collections/2014/11/11/pale-armistice/

Hawthorn, Jeremy. A Glossary of Contemporary Literary Theory, 4th Ed. London, Bloomsbury Academic, 2000

Hughes, Philip (2015) Rozanne Hawksley website, retrieved on 10 August 2015 from http://www.rozannehawksley.com/page3.htm accessed May, 2015

Hurlstone, Nigel. “Drawing and the Chimera of Embroidery.” Machine Stitch Perspectives. Eds. Alice Kettle, Janet McKeating. London: A + C Black, 2010: p36

Keating, Paul. “The Redfern Address”, 1992, at ABC website archives, retrieved August, 2015, http://www.abc.net.au/archives/80days/stories/2012/01/19/3415316.htm

Kentridge, William. “Anything is possible: William Kentridge.” PBS Documentary art21. USA. Retrieved ABC i-view March, 2013.

Kovacs, Tania (ed.). The Drawing Book: A Primary Means of Expression. London: Black Dog Publishing, 2007: p.209

McCrickard, Kate. William Kentridge, Modern Artists. London: TATE Publishing , 2012: p.45

Merleau Ponty, Maurice. The Merleau Ponty Aesthetics, Illinois: North-west Press, 1993:p.127 cited by Hurlstone, Nigel. “Drawing and the Chimera of Embroidery.” Machine Stitch Perspectives. Eds. Alice Kettle, Janet McKeating. London: A + C Black, 2010:p.36

Merleau-Ponty, Maurice. Phenomenology of Perception, New York, Routledge Classics, 2002.

Ravenscroft, Alison. The Postcolonial Eye: White Australian Desire and the Visual Field of Race, United Kingdom: Ashgate Publishing, 2012: p1; p. 8-9; p.18

Reynolds, Henry. Forgotten War, Sydney, New South Publishing, 2013: p.16

Rudd, Kevin, Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade Website, retrieved on 29 June 2015 http://dfat.gov.au/people-to-people/public-diplomacy/programs-activities/Pages/speech-by-prime-minister-kevin-rudd-to-the-parliament.aspx

Russell, Lynette. Roving Mariners: Australian Aboriginal Whalers and Sealers in the Southern Oceans 1790 – 1870, State University of New York, 2012: p.20

Stanner, William Edward Hanley. The Dreaming and Other Essays, Collingwood, Black Inc. Books 2011:p.24

Sullivan, Graeme. Art Practice as Research: Inquiry in the Visual Arts, Sage, 2010: 245

Young, Robert JC. “The Void of Misgiving.” Communicating in the Third Space. Eds. Karin Ikas, Gerhard Wagner. New York, Routledge, 2008, p.82

About the Author

Julie Montgarrett is an artist, curator and lecturer at Charles Sturt University, Wagga Wagga, NSW whose practice includes solo and group exhibitions, site specific installations, and community-based arts projects in Australia and internationally. Her main research interests are in the areas of drawing and textile in testing the conceptual and spatial possibilities of visual narratives to question dominant Australian histories exploring doubt and fragility in complex installations